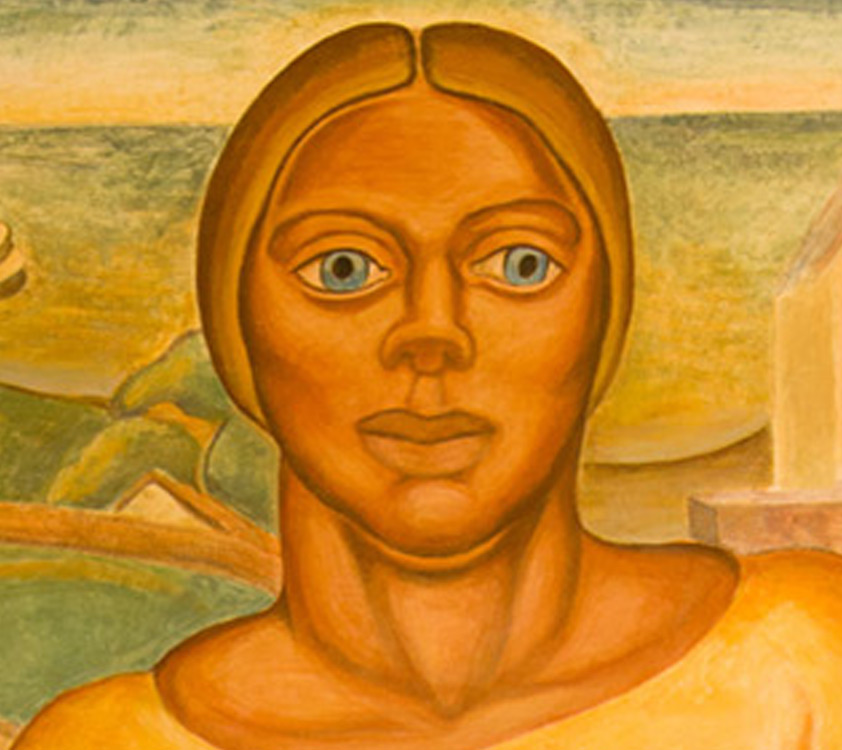

Conrad Albrizio painted the four panel fresco on the North portico of the Louisiana State Exhibit Museum during the summer of 1938. The artist selected two monumental iconic figures – female and male – to represent contrasting Agriculture and Industry of the state of Louisiana. The side panels illustrate the predominate activities in North and South Louisiana. Designed to face U.S. Highway 80, Greenwood Road, the artwork introduces the visitor to the thematic content of the museum itself – a celebration of Louisiana’s labor and economy – hallmarks of the Depression Recovery movement. Today, the value of this art is beyond calculation.

Born in New York City in 1894, Conrad Albrizio is an important figure in American art. He studied at the Art Students League in New York, researched the fresco technique in Europe, and served on the faculty at LSU from 1935 until his retirement in 1954. The WPA commissioned Abrizio to paint murals in New York, Detroit, Alabama and Louisiana. Huey Long selected him to paint murals in Baton Rouge’s new capitol building in 1932. Albrizio also contributed work to the DeRidder Post Office and the Union Passenger Terminal in New Orleans. He died in Baton Rouge in 1973 at the age of 79. You can read more about Albrizio here.

Some framing questions for how to approach these Frescos may be downloaded here. These questions may be of particular interest to teachers looking to introduce the subject of local art to their classes. LSEM Fresco Questions

The Technique of Fresco Painting

Albrizio executed the LSEM mural in true fresco technique – applying oil paint directly to wet plaster. Fresco is the Italian word for “fresh,” indicating that the paint is applied to fresh plaster. Frescos are a part of the building itself, and will last as long as the wall itself will.

Many artists avoid painting frescos, as they require a high level of skill and a large continuous commitment of time. A layer of plaster will dry in 10-12 hours. An artist would begin painting after one hour and continue until two hours before the drying time. Thus, an artist would need to know exactly how much he could paint in those hours, before the plaster dries. Unlike oil painting, once the image is on the plaster the only way to change it is by removing the plaster and starting again.

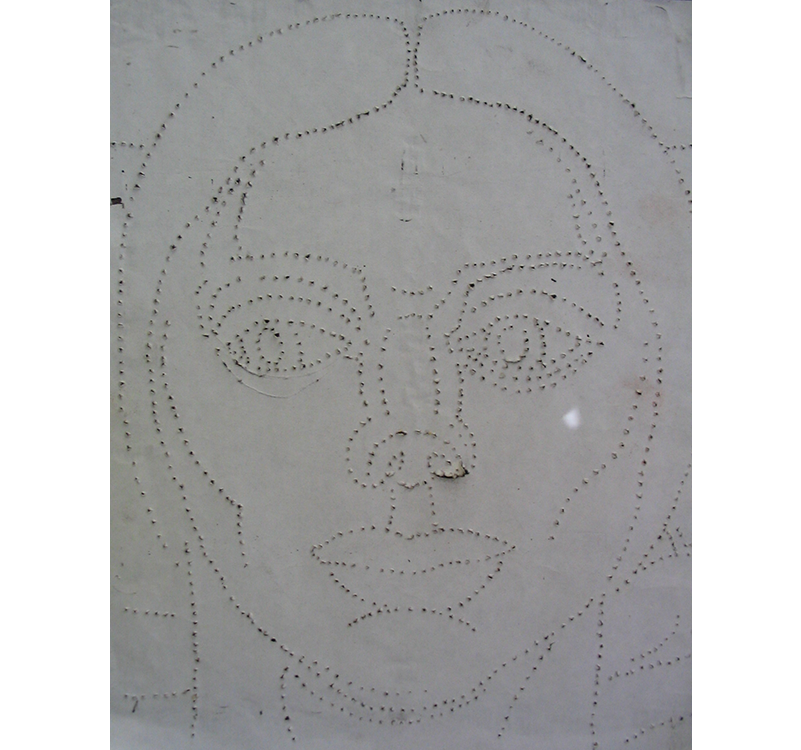

To aid in the process, Fresco artists use “cartoons” to map out their designs prior to beginning the painting process. Cartoons are drawn on regular paper with pencil, charcoal, chalk, etc. After coating the wall with white plaster, the artist transfers a section of the cartoon to the wet plaster. Finally, the artist must apply colors within the cartoon quickly, before the plaster dries. Small sections of the cartoon are completed before moving to another part of the wall.

Frescos on dry plaster began in ancient Egypt and Greece. True fresco exists in Roman cities like Pompei, but also developed much earlier in Mexico. The people of Teotihuacan used fresco technique in the grand temples as well as in houses. The ancient Mexicans particularly loved bright colors and used red, yellow, jade green and bright blues. The most famous fresco is Michelangelo’s Renaissance ceiling of the Sistine Chapel in Rome. Revived in the 20th century, mural painting had become a popular art form across the country during the 1930s.

Conservator Elise Grenier created these steps in the Fresco process to illustrate the artist Albrizio’s technique. She used the allegorical figure of Agriculture from the east wing of the portico mural.

Cartoon

Cartoon transferred to plaster by dotting

Painting into wet plaster on a wall or other surface

Final Product

Conservation

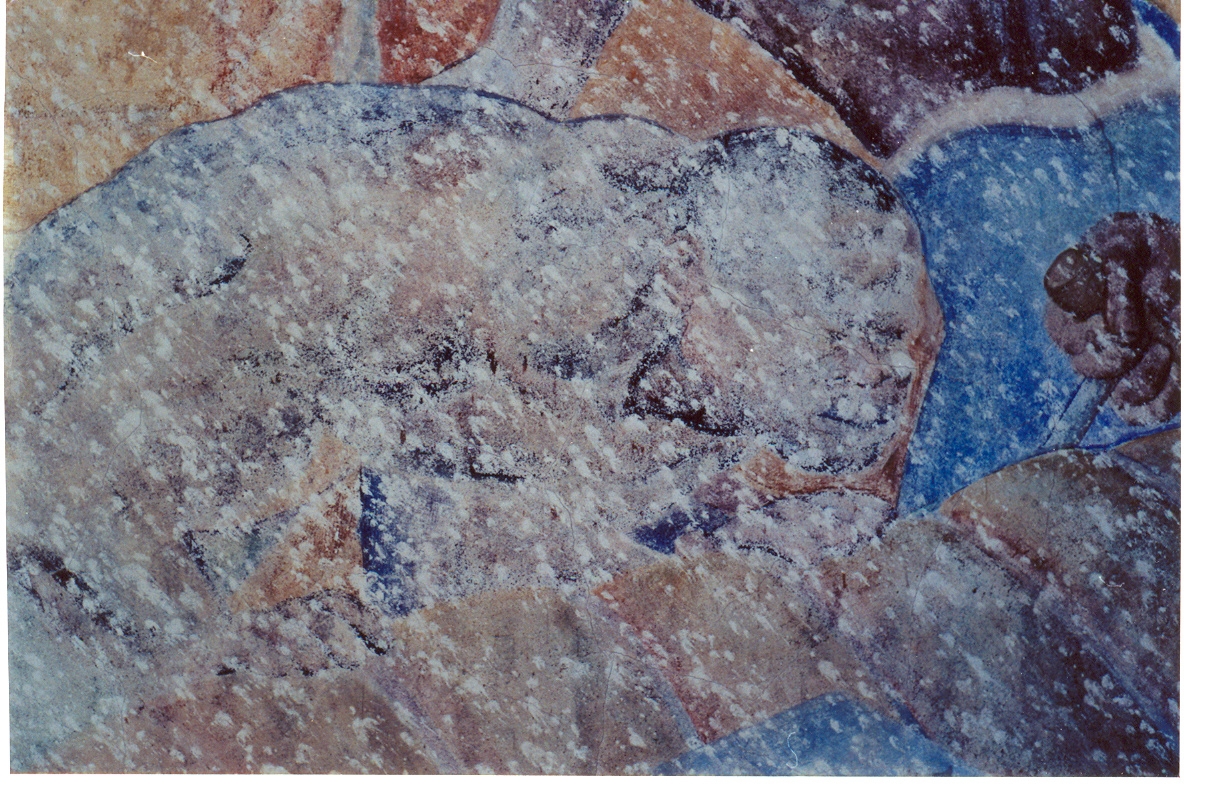

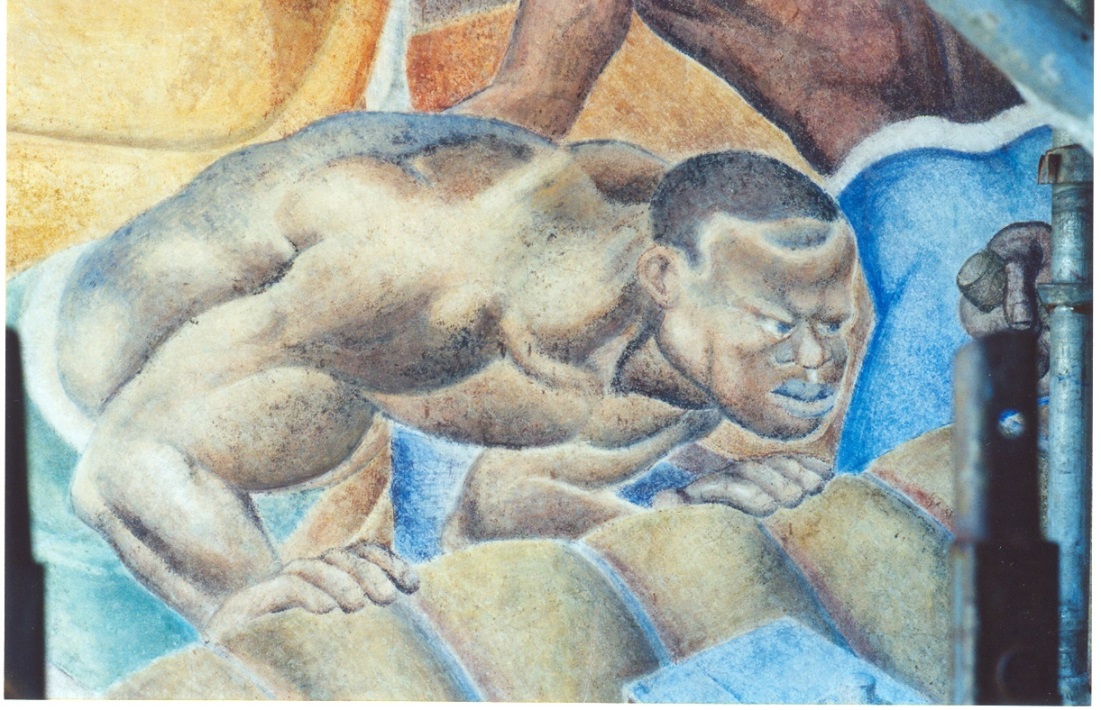

Because the museum’s frescos are partially exposed to the elements, they frequently suffer damage from wind, humidity and temperature. During the 1950s, Mrs. Ben Gray, an art teacher at Fair Park High School, repaired damage to the mural from vandalism. In 2000, a hail storm resulted in severe loss of paint from the east panel. In 2002, Elise Grenier, of Grenier Conservation, made a remarkable recovery of the lost paint. Again in 2009, excessive rainfall standing on the roof caused leaks that stained the Agriculture figure. Ms. Grenier returned to conserve the fresco in 2010. She expertly removed soluble salt crystals that caused the paint to flake from the surface. A Louisiana native, Ms. Grenier is a professional conservator, who works primarily in Italy on 15-16th century fresco artworks.

Detail of a cotton worker on the LSEM Fresco, before and after restoration. Photographs by Elise Grenier.